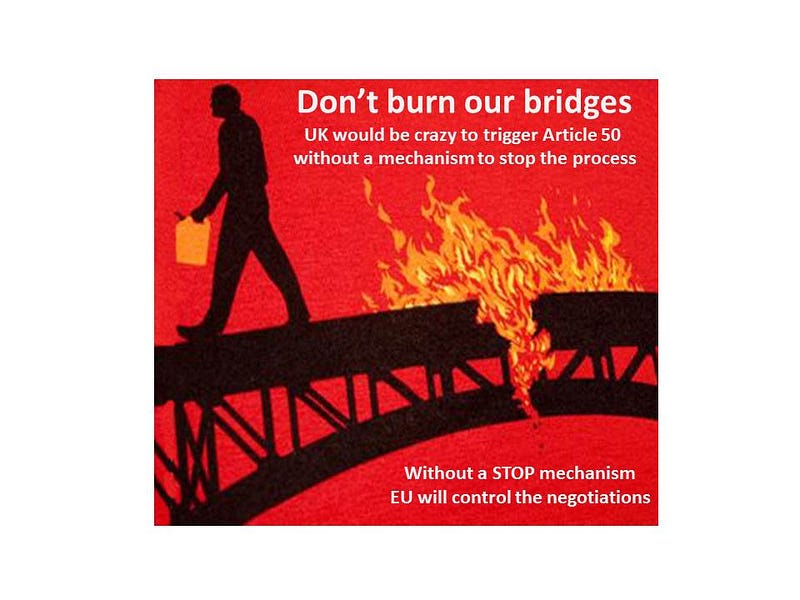

Either don’t trigger A50 at all or at least build in a mechanism to stop the withdrawal if the exit deal not in the UK’s best interests.

If the UK enters negotiations with the EU without the ability to stop the process the EU negotiators will hold all the negotiating power.

At present the wording of Article 50 is silent on the possibility for the UK to withdraw it’s notification to leave the EU once given. It has commonly been accepted that this means the UK cannot withdraw notification once given.

The author believes that it would be irresponsible of the UK to enter into exit negotiations with the EU without the ability to stop the process should it become clear that leaving is not in the UK’s best interests.

This paper examines how the UK can gain agreement from the EU for the UK to have a ratification process at the end of negotiations.

The House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution have recently release a report on — The Invoking of Article 50 12th. Sept 2016. As the most authoritative and independent review available, the author refers to this report throughout this paper.

It is generally accepted that if the UK had a method of stopping the EU exit process (triggered by notification under Article 50) it would strengthen the UK’s negotiating position however, the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution recommend that the UK assume that Article 50, once triggered, cannot be withdrawn without the agreement of the EU.

However the HoL report does also go to explain that the UK will particularly strengthen the legal position if they enact primary legislation to define how they will operate the Article 50 process and the UK will have a strong case to argue that any mechanisms enshrined with an Act of Parliament form our “constitutional requirements”.

This paper suggests the UK does indeed enact primary legislation to define the Article 50 process and include 2 checkpoints:

Checkpoint 1

If there is no sensible deal possible then the process may end here and an expensive negotiations exercise is avoided.

It is there is the possibility of a sensible deal then Article 50 will be triggered and the negotiations will take place.

Checkpoint 2

At the end of the negotiations their will be a democratic decision taken whether to ratify the Exit deal or not. This might take the form of a Parliamentary vote, a further (2nd) referendum or in a General Election with the candidates in each constituency either supporting or opposing the deal on offer.

The UK may decide to continue with the exit terms negotiated and leave the EU.

Should the democratic decision of the UK be that the deal on offer is not in the UK’s best interests then the UK would be able to withdraw it’s notification and stop the withdrawal process.

Rationale for a Checkpoint 2

There is a very real possibility that, without change, the UK is heading for a very Hard Brexit whether we want it or not.

If we “just do it” and trigger Article 50 notification of the UK’s intent to leave the EU as the John Redwoods et al encourage us then we effectively trigger a Hard Brexit. As soon as the UK notify the EU of our intent to leave the EU under Article 50 (2) we effectively hand over all negotiating power to the EU. They could, in theory, just let the 2-year clock run down and the UK would cease to be a member of the EU and no longer a party to the EU treaties.

It is hard to imagine a better way to ensure that Brexit is Hard than to trigger Article 50 without the ability to reverse the UK’s notification.

By providing for a democratic ratification process for the UK at the end of the negotiation process the UK will have the ability to stop and indeed step away from the withdrawal process should it be necessary.

The House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution have recently examined this matter and concluded that:

It is unclear whether a notification under Article 50, once made, could be unilaterally withdrawn by the UK without the consent of other EU member states. In the light of the uncertainty that exists on this point, and given that the uncertainty would only ever be resolved after Article 50 had already been triggered, we consider that it would be prudent for Parliament to work on the assumption that the triggering of Article 50 is an action that the UK cannot unilaterally reverse.

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution Report — The Invoking of Article 50 12/9/16 page 5 para 13

It would seem an eminently sensible approach for the UK to assume that notification under Article 50 (2) cannot be withdrawn without agreement from the EU.

Notwithstanding this caution, it is worth considering how much better our negotiating position would be if we could get the EU to agree that the UK could withdraw notification. It is a prize worth fighting for and it will avoid the nightmare scenario of the UK defaulting into a Hard Brexit as the negotiating period runs out.

Act of Parliament, Resolution or Motion?

The key dependency upon this approach working is that the Government accept that they need to involve Parliament. They are currently arguing that they can trigger Article 50 notification, undertake negotiations and withdraw from the EU using powers reserved under the Royal Prerogative.

This stance is being challenged in the Courts and the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution, after taking evidence, have concluded that to continue with this position would be foolhardy:

It would be constitutionally inappropriate, not to mention setting a disturbing precedent, for the Executive to act on an advisory referendum without explicit parliamentary approval — particularly one with such significant long-term consequences. The Government should not trigger Article 50 without consulting Parliament.

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution Report — The Invoking of Article 50 12/9/16 page 8 para 24

The select Committee then review the appropriateness of an Act of Parliament, a Resolution or a Parliamentary motion in defining the Article 50 process.

An Act of Parliament would ensure that any constitutional uncertainties are avoided, and make certain that Parliament has the opportunity properly to debate the issues at hand and define in law the “constitutional requirements” that must be met before

Article 50 is triggered. Resolutions would allow Parliament swiftly to demonstrate its position on the triggering of Article 50, while — in the case of a motion simply setting out that position — keeping that issue separate from wider debates about Parliament’s proper role in the negotiation process.House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution Report — The Invoking of Article 50 12/9/16 page 15 para 44

It is clear that an Act of Parliament is the most appropriate vehicle in order to define our “constitutional requirements” in law. As this phrase is key to gaining the EU acceptance of a ratification step for the UK it is essential that the UK do indeed enact primary legislation through an Act of Parliament for this Article 50 process.

Advantages to HMG in introducing legislation for Article 50 process

The Government are facing legal challenge, censure from the House of Lords, and Parliamentary revolt when they do eventually have to enact or repeal some law. It would seem like a sensible path for Government to adopt an approach that avoids these obstacles. The most appropriate route would appear to be the introduction of an Act of Parliament to manage and control the negotiation process.

However , as it stands, the Government might feel that trying to take primary legislation through Parliament with their slender majority and the groundswell of Remain public opinion might actually be an impossible task. However there is a way to structure the legislation that would bring the moderate Leavers and Remainers in both Parliament and the country along with them.

The fact that the UK would have the option to walk away from the negotiations will improve the possibility of negotiating a reasonable agreement.

The Select Committee report does confirm that the UK could use the Act of Parliament to improve it’s legal standing when triggering Article 50 and the author believes we could also use the Act to control a Ratification process at the end of negotiations and this too would then become part of the UK’s“constitutional requirements”

Given the nature of the UK’s constitution, resting as it does on Acts of Parliament, convention and common law, the contents of any legislation would become part of the UK’s “constitutional requirements” for the purposes of Article 50. This means that Parliament could choose to set out requirements that would allow it to take control of the process by which Article 50 was to be triggered. For example, an Act could state that Parliament authorised the UK Government to trigger Article 50 if — and only if — the Government had first presented for parliamentary approval its proposal for the UK’s new relationship with the EU on the basis of which it intended to negotiate. We note in addition that if Parliament required the Government to meet certain prerequisites before Article 50 could be triggered, it would strengthen the Government’s position against those in the EU who argue that no negotiations, even informal, should take place before Article 50 has been invoked.

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution Report — The Invoking of Article 50 12/9/16 page 10 para 32

The Select Committee recommend the first checkpoint i.e. the ability to call a halt before notification under Article 50.

The author recommends including a second checkpoint where the UK can ratify the deal(s) following negotiations.

This two checkpoint approach would strengthen the UK’s position to negotiate before we trigger Article 50 and it follows that we can also strengthen our position during and after negotiations as well.

It is important to note that even if acceptable terms are agreed, Article 50 requires that the other 27 EU members would need to ratify the agreement. If they cannot ratify the agreement then, unless we have the ability to stop the process, the UK would just cease to be a member without any agreement.

If we want to have a soft landing then the UK must be able to withdraw it’s notification under Article 50 (2) if either the UK or the EU cannot ratify the deal(s) on offer.

Why would the EU agree to the UK being able to withdraw notification of it’s intent to leave the EU?

The challenge that has come from many quarters is why the EU would agree to such a mechanism as it obviously weakens their own position?

Well, despite statements made during the Referendum campaign, the EU is deeply democratic and utterly predicable. It is my contention that if the mechanism is correctly structured, the EU would not be able to refuse.

For the UK’s ratification step to gain EU acceptance the approach will need to demonstrate that it is:

- Compliant with Article 50

- “in accordance with the Member State’s constitutional requirements”

- Fair to EU citizens

- Non-discriminatory between nationalities

- Democratic

If the UK present a plan/approach that meets these criteria the EU will support it, in fact it would be utterly incredible for them to do anything else.

Similarly the European Court of Justice could intervene and interpret Article 50 as not permitting a notification, once duly given, to be withdrawn. But to reach that decision — which is not to be found in any overt provision — in the teeth of a democratically enacted law by a national Parliament which has a wholly democratic final decision — would itself be damaging to the reputation of the EU.

So, does the plan as outlined meet this criteria? Let’s take them one at a time:

1. Compliant with Article 50

We will need to frame our approach to conform with Article 50.

Article 50 Section 4 provides for a ratification process for the Union members and it would be very difficult indeed for the EU to argue that the UK should not provide for a similar, wholly democratic ratification step themselves.

2. “in accordance with the Member State’s constitutional requirements”

This is the key point in Article 50. As the UK does not have a single written constitution, Parliament is the supreme decision-making body — and since this situation has not previously arisen, it is for Parliament to decide on those constitutional arrangements.

Given the nature of the UK’s constitution, resting as it does on Acts of Parliament, convention and common law, the contents of any legislation would become part of the UK’s “constitutional requirements” for the purposes of Article 50. This means that Parliament could choose to set out requirements that would allow it to take control of the process by which Article 50 was to be triggered.

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution Report — The Invoking of Article 5012/9/16 page 10 para 32

If the UK approach is encompassed by an Act of Parliament it can set out whatever steps felt necessary and again the EU would find it very difficult to challenge. These will become our “constitutional requirements”.

3. Fair to EU citizens

This includes being fair to UK UK citizens. Article 50 provides for the other member states to ratify, by qualified majority, the deal being offered to the UK. If our UK Withdrawal from the EU Bill provides a ratification process for the UK citizens it will be seen as fair.

4. Non-discriminatory

If the ratification process is to involve a popular vote then it would be expected that all EU citizens directly impacted would have a vote. This would extend the electorate beyond the UK, Eire, Malta and Cyprus to include all EU citizens resident in the UK plus all UK citizens living outside the UK. With this enfranchisement such a popular vote would not be challenged by the EU.

5. Democratic

UK could satisfy the requirement to be democratic by having a vote as part of the ratification process. This might take the form of a Parliamentary vote, a further referendum (with the electorate as outlined above) or in a General Election with the candidates in each constituency either supporting or opposing the deal on offer. Any of these options would be seen as wholly democratic and not subject to challenge.

Summary

In the scenario outlined above the ratification decision will have been sanctioned and controlled by UK law, as recommended by the HoL Select Committee on the Constitution and the EU would, with their inherent democratic and fair-minded structure have to accept the process including the two defined checkpoints thus providing the UK with the ability to stop the process if the UK so wish.

As Sir David Edward told the House of Lords in May 2015** “It is absolutely clear that you cannot be forced to go through with it if you do not want to: for example, if there is a change of Government.” and the UK would remain in the EU.

*****************************************************************

References

*Richard Tunnicliffe discusses this in his blog site in an article Negotiation Brexit — Shades of Article 50 @howshouldwevote.

** The EU Committee of the House of Lords considered this question in its report on “the process of withdrawing from the European Union” published on 4th May.